The American Zonophone Discography: A History of American Zonophone, 1900–1912

By Allan Sutton

The introduction of Zonophone as a competitor to Berliner’s Gramophone in the late 1890s, and the legal battles that ensued, make up a complicated tale that will be left for the companion volume in this series. Our concern in this volume is with the events leading up to, and following, Eldridge R. Johnson’s acquisition of the Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing Company in 1903.

By 1900, the Universal Talking Machine Company was producing records and phonographs of reasonably good quality but was hampered by lack of patent protection. The American Graphophone Company (Columbia), which was looking to enter the disc market but had not yet developed its own disc products, agreed to license Universal Talking Machine in June 1900, and Columbia dealers began to handle the Zonophone line.1 The agreement provided Universal some protection under Columbia’s Bell-Tainter patent,2 but the relationship was short-lived. By the autumn of 1901, Columbia had its own discs and phonographs on the market, and with no further use for Zonophone, the company set out to undermine what was now a competitor.

On December 19, 1901, Universal’s manufacturing arm was reorganized and chartered as a new corporate entity, the Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing Company.3 The new firm was not licensed by Columbia, which lost no time in taking legal action. On March 17, 1902, Columbia filed a lawsuit charging Universal with infringement of its Bell-Tainter patent. Judge Lacombe, after granting a preliminary injunction in September 1902, then temporarily suspended it. Hearings resumed two months later, and on November 25 Lacombe issued an injunction prohibiting the manufacture, use, and sale of records by Universal Talking Machine.

Injunction in hand, Columbia took its battle directly to Zonophone dealers, serving them with papers enjoining them from selling Zonophone records. Violators were ordered to deliver their Zonophone inventory to judicial custody for destruction, with an accounting for damages to follow. Universal offered to pay the legal costs of any dealer sued by Columbia,4 but the threat of legal action was sufficient to drive many away.

By early 1903, with Zonophone records fast becoming unsalable, Universal sent a letter to dealers promising that it was “preparing to supply records made by a process not enjoined.”5 That spring, Universal vice-president Frank. J. Dunham approached the Gramophone & Typewriter Company, Ltd. (Victor’s English sibling) about a possible sale of his company. In April G & T began formal negotiations for the purchase of the Universal Talking Machine Company, the Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing Company, and the latter’s share in the International Zonophone Company. The initial offer was made through Deutsche Grammophon (G & T’s German affiliate in Berlin), acting as G & T’s agent. After two months of bargaining, an agreement was finally reached to sell the Universal Talking Machine Company to G & T. The sale was settled on June 6, 1903, and the change of ownership became official on August 1.

Once the sale was completed, G & T general manager William Barry Owen approached Victor president Eldridge Johnson with an offer to sell him a controlling interest in the Universal Talking Machine and Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing companies. Johnson, although reportedly unenthusiastic about the prospect, realized that the purchase would hand him control of a potentially troublesome competitor. An anonymous recording-industry official told the Music Trade Review, a bit prematurely,

I am reliably informed that a consolidation of certain talking machine interests has already been consummated, namely, that Eldridge Johnson, president of the Victor Talking Machine Co., has acquired a controlling interest in the Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing Co., though his name does not figure in the deal as yet.6

The same source claimed that International Zonophone would “continue its European business as hitherto under the management of [Frederick Prescott]; but what other plans were in the wind no one would be fully informed until Mr. Owen reached New York.” Owen sailed for New York in late July to seal the deal. He had barely arrived when, on August 8, it was announced that Prescott had resigned his position with International Zonophone.7

Owen’s arrival in New York aroused a surprising amount of interest, and his activities were closely watched. The trade papers were quick to report that Owen and Victor’s Albert Middleton had been spotted entering the Universal Talking Machine offices. Speculation ran rampant, fueled in part by Owen’s evasiveness. A reporter who encountered him at the Waldorf-Astoria on August 21 was unable to obtain any information. “As a matter of fact, I haven’t a word to say yet,” Owen told him. “I certainly want to get all the publicity I can when negotiations are completed.”8 When later asked whether Eldridge Johnson was involved in some way, Owen simply responded, “Why not ask Mr. Johnson? He knows.”9 But Johnson was not talking, either.

The news that Johnson would indeed purchase the U.S. rights to Zonophone was leaked on September 12, 1903, before negotiations were completed. Within several days it was confirmed that the Gramophone & Typewriter Company would retain control of the Zonophone brand in England, where Zonophone would be purely a G & T product. “Now all Zonophone records are made by Gramophone engineers and the records are finished at the Gramophone factory and pressed by the Gramophone Company,” a German reporter informed the Music Trade Review in January 1904. “Excepting for the name Zonophone, which they bear on the label, they are Gramophone records.” The same report stated, in error, that Owen was going “permanently to America.”10

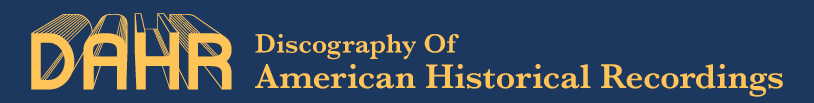

For $135,000, Johnson received G & T’s controlling interest in the Universal Talking Machine and Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing companies and would now control the Zonophone brand in the United States, U.S. holdings, Mexico, and Cuba. There is a widely held misconception that the Victor Talking Machine Company purchased Universal Talking Machine, but that was not the case. The Victor Talking Machine Company neither purchased nor owned Universal Talking Machine. No doubt anticipating further legal attacks on Zonophone by Columbia, Johnson wisely decided to keep Victor and Universal separated. Victor vice-president Leon Douglass made the situation clear in a letter to the trade dated October 7, 1903:

Owing to the many rumors that the Victor Co. has purchased the Zonophone Co., we have decided to make the following statement: — The Victor Talking Machine Company does not own the Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing Co., but Mr. Eldridge R. Johnson, President of the Victor Co., owns a large block of stock in the Universal Co. The two companies are entirely separate and independent, are competitors, and, so far as we know, will continue to be competitors.11

Johnson now found himself in control of two competing companies that offered similar material in much the same market. He had little involvement (and by most accounts, little interest) in his newly acquired company, allowing it to operate independently. Its executive staff consisted of Henry B. Babson (president), J. A. McNabb (vice-president and general manager), and F. A. Crandall (secretary), none of whom were employed by or answered to the Victor Talking Machine Company. Universal Talking Machine’s own studio had been in operation for several years, and its pressing was being handled by the independent Auburn Button Works. Fred Hager, who had been with the company almost from the start, stayed on as musical director, a position he held through March 1906.

Nevertheless, signs of new ownership became apparent during early 1904. In February the company set a new sales record and moved into much larger quarters at 28 Warren Street in New York. It soon terminated its relationship with the Auburn Button Works,12 turning its pressing work over to the Duranoid Company, an independent plant that had pressed for Berliner and was currently handling Victor’s overflow. The transition was marked by the introduction of a redesigned label, and noticeably improved pressings, in April 1904.13 Promotional efforts were stepped up, and special souvenirs and a million promotional folders were produced for distribution at that summer’s World’s Fair in Saint Louis. At the same time it was announced that after July, new releases would be announced monthly, rather than bimonthly.14

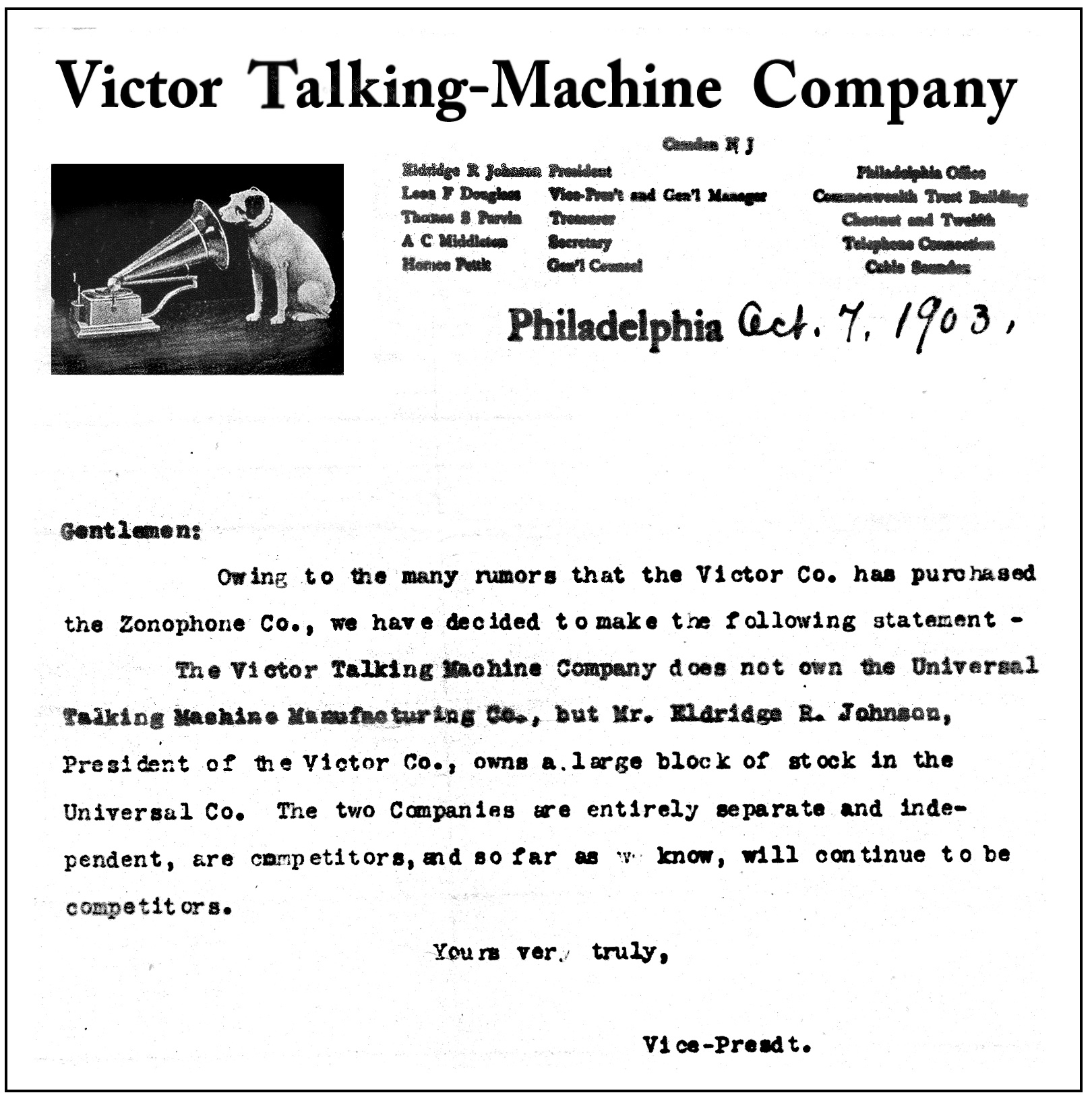

By the autumn of 1904 there were plans to introduce a ten-inch Zonophone disc. So far, the records had been produced only in seven- and nine-inch form, with the occasional eleven-inch special. The discs would be priced at $1 each, the same as Victor’s black-label records. The new ten-inch line, commencing at #1 and pressed by Duranoid, was announced in November 1904, and the first twenty-five numbers were released the following month. The price remained at $1 into late 1905, when it was slashed to 60¢, in line with general price-cutting that was taking place throughout the industry. The price dipped to 50¢ in December 1905 but returned to 60¢ in late 1906, where it remained until single-sided discs were discontinued. Like other record manufacturers of the period, Universal strictly enforced its pricing and occasionally prosecuted dealers caught selling below list price.

Its low pricing probably hampered Zonophone’s ability to hire the sort of talent that was available to Victor, which could afford to lure celebrity artists with generous retainers and royalties, the cost of which were reflected in their high retail prices. Instead, Zonophone relied heavily on its house musicians, and low-cost studio freelancers like Len Spencer, Ada Jones, and Billy Murray, to fill the catalog.

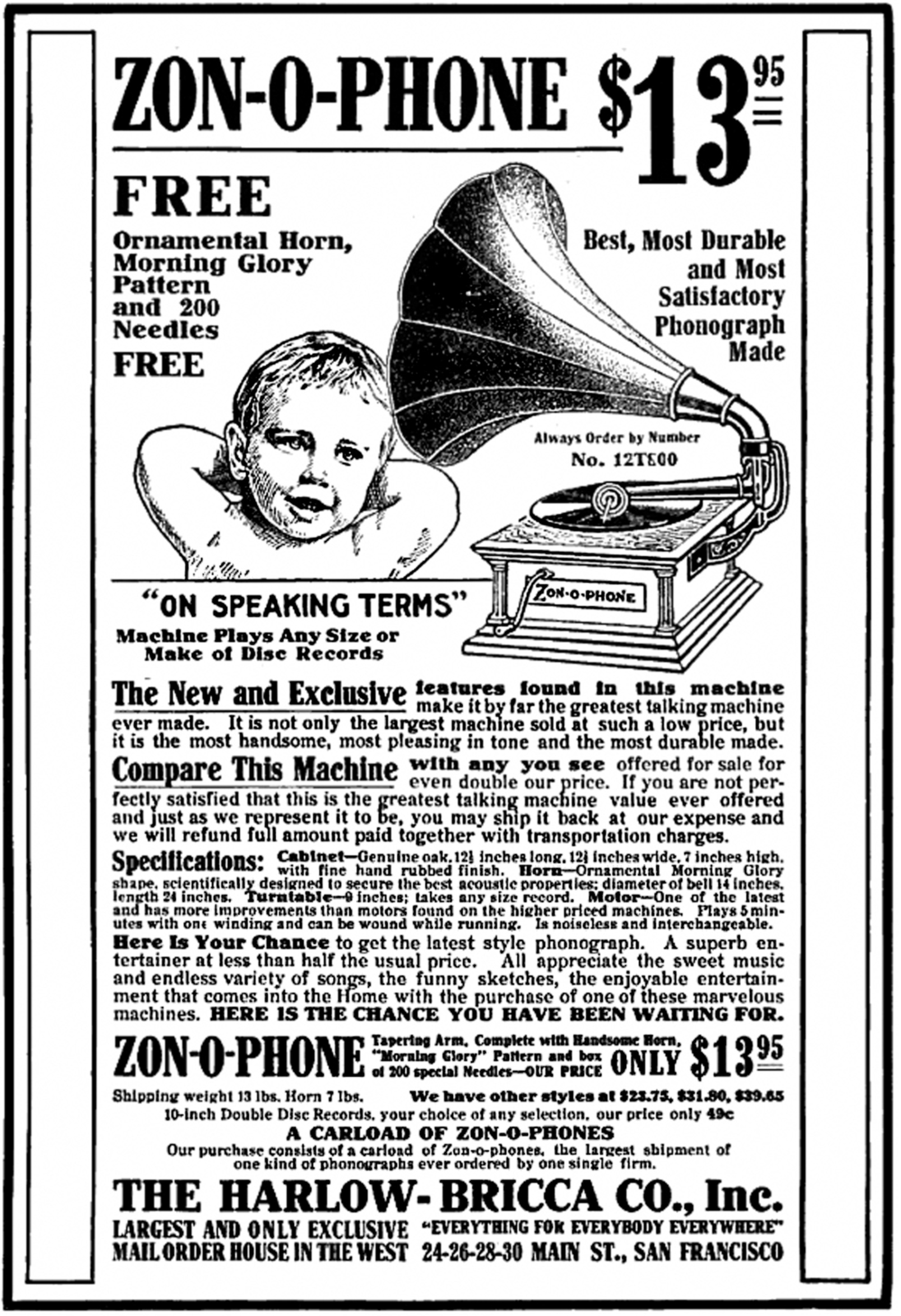

Although the new Zonophone products bore no mention of Victor, the connection was obvious in the addition of Victor’s patents to the reverse-side warning labels, and the introduction in late 1904 of a new line of Zonophone machines that incorporated Eldridge Johnson’s tapering tone-arm.15 Johnson guarded the tapered arm jealously. Prior to the introduction of the new Zonophone line, it had been employed legally only on Victor machines, and Johnson went on to vigorously prosecute any company that was foolish enough to infringe his patent. Universal originally advertised the new tapered-arm machine at $30, only to discover after completing the first production run that they had priced it too cheaply. On Christmas Eve 1904 the company broke the news that it was raising the price by $5, telling dealers, “It is unnecessary to assure you that it is well worth the difference in price. (It should never have been listed at $30.)”16

On March 1, 1905, the receivers for the National Gramophone Corporation (Zonophone’s original distributor) auctioned their remaining inventory of now-antiquated pre-Johnson Zonophone discs.17 Production of new seven-inch records was quickly discontinued, although some existing seven-inch masters continued to be pressed until January 1906. The first annual Zonophone catalog to be issued under Johnson’s ownership, in November 1905, was devoted largely to the new ten-inch records.18 A month after the catalog’s release, the company announced that production of nine-inch discs was to be discontinued “in sixty days,” after which the remaining stock would be used only in conjunction with premium plans.19 Twelve-inch Zonophone discs were a longer time coming. They were finally announced to the trade in January 1907 (although they were not available until March of that year)20 and were never produced in great quantity.

By 1906 Zonophone records were selling very well. In January San Francisco distributor Kohler & Chase placed the largest single order to date, comprising 165,000 discs that were shipped cross-country in seven rail cars. The Talking Machine World for that month reported that with orders for 200,000 additional records on hand, Universal was planning to add at least twenty-five new presses, and (as had been announced two months earlier) would discontinue the seven- and nine-inch discs.21

By March 1906 Universal was making plans to move to larger quarters. In May the company began consolidating its factory and general offices in a four-story building at Mulberry and Camp Streets in Newark, New Jersey.22 The new headquarters were located near the Duranoid pressing plant, which Universal purchased outright at the time of the move. The recording studio, export department, and some sales offices remained in New York. Shortly before the move, musical director Fred Hager resigned to devote more time to his music-publishing business, but he gave Zonophone permission to continue releasing band recordings under his name.23 His place was taken by Edward King, a percussionist who had been a member of the house orchestra for several years.

Eldridge Johnson spent the autumn of 1906 in London, consulting with Gramophone & Typewriter Company officials. While there, Johnson convinced G & T executive Belford G. Royal to take over management of Universal Talking Machine. Their return to the states marked the beginning of a significant shake-up at Universal. In November, Henry Babson resigned from the company, and Royal took over as president.24 A short time later, A. C. Middleton was installed as secretary. For the first time, Universal was being overseen by Johnson’s close associates. Both had begun their careers in Johnson’s machine shop during the Berliner days. Royal went on to set up what would become the Gramophone & Typewriter Company in England, while Middleton served as Victor’s first secretary. At the same time these appointments were announced, Henry J. Hagen (who had been in charge of joint Victor-Zonophone foreign recording expeditions) was named manager of the Zonophone studio.25

While in London, Johnson had also arranged to license G & T’s recordings of complete operas, made by members of the La Scala company in Milan. In November The Talking Machine World announced that these were to be issued on American Zonophone,26 but Johnson apparently had a change of heart. Most of the records were instead assigned to Victor, which announced their first release of the material in the same month that TMW made its erroneous announcement.27

Zonophone’s infant-and-phonograph trademark, captioned “On Speaking Terms,” was introduced to the public in early 1907. Although widely used in advertising, it would not appear on records until late 1908, when Zonophone’s labels were redesigned for the new double-sided pressings. Universal had experimented with some unlikely trademarks before settling on the baby, including a depiction of a Sphinx with the legend, “It Would Move a Heart of Stone.”28 A proposed monkey-and-phonograph trademark with the legend “Almost Human” was widely derided in the trade papers. The Music Trade Review commented, “Mr. Monk is supposed to be lost in admiration from the caressing manner in which he embraces the horn and reflectively scratches his adorable phiz.”29 Neither trademark ever appeared on a Zonophone label.

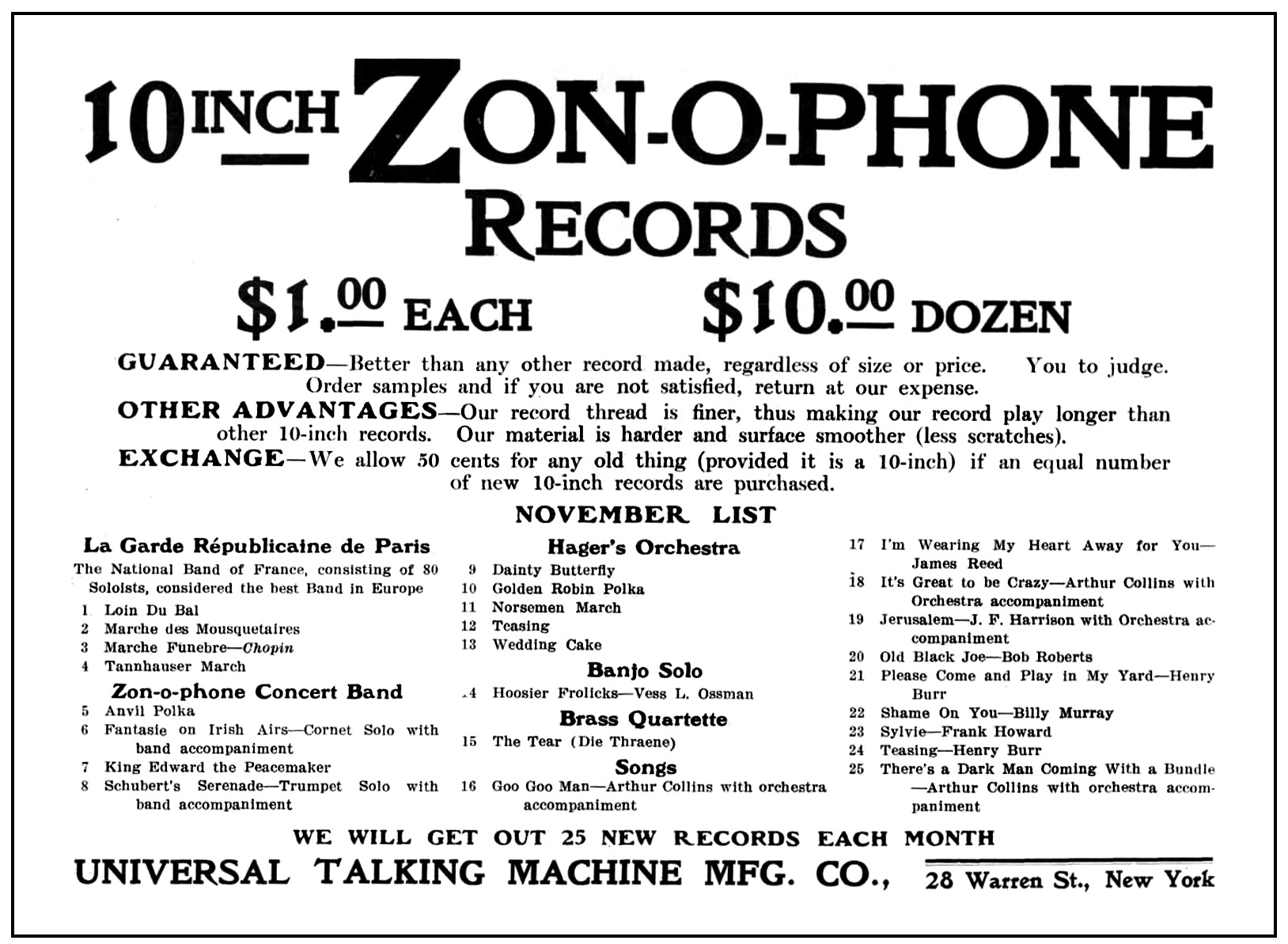

Zonophone attracted considerable attention in March 1908 with its “Extra! Special! No. 2” supplement. The occasion was the release of highlights from The Merry Widow and A Waltz Dream. The aggressive marketing campaign took some liberties with the truth, claiming that the recordings comprised “ALL the music” from The Merry Widow, sung and played exactly as on stage.30 In fact, Zonophone offered only selected numbers, and the performers were the usual studio free-lancers and house orchestra. Nevertheless, Zonophone’s mastery of marketing hype allowed them to eclipse other companies’ versions of the same material.

Special No. 2 also included five recordings by soprano Luisa Tetrazzini (originally made in 1904 on nine- and eleven-inch discs), which Zonophone resuscitated in connection with the soprano’s celebrated visit to New York. Victor had yet to release any Tetrazzini material, so for a short time Zonophone had the diva to themselves in the American market. The Talking Machine World reported that demand for the Supplement No. 2 records “has been so far in excess of the company’s expectations that [they] have been and still are completely swamped with orders.”31

Zonophone’s export department expanded during this period, under the direction of sales manager J. D. Beekman. In January 1908 Beekman embarked on what was to have been his most ambitious sales trip so far, taking him on a six-month journey from Newark to the West Coast, and then on to Mexico and Cuba, where the Disco Zonofono export line was selling well. Beekman got as far as Portland, Oregon, before he was taken ill in April and ordered home by his attending physician.32

Early 1908 also saw a general house-cleaning in which many of the slowest-selling sides were deleted from the ethnic and popular catalogs. Much of the latter consisted of outdated comic and topical songs. At the same time, Zonophone gave some hoary old “standards” new life, reporting that those suffering from “questionable tone” had been remade using an improved process.33

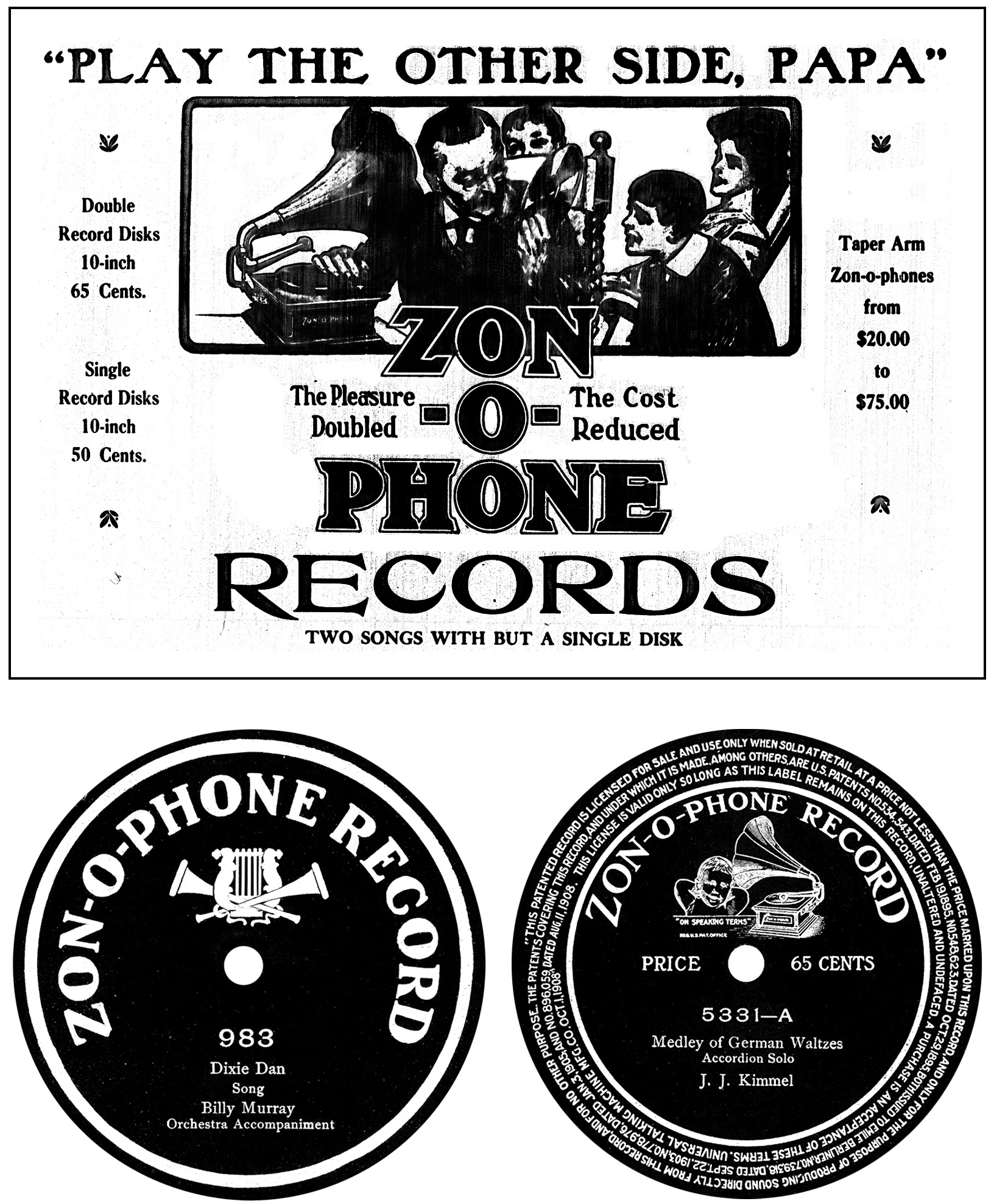

On September 10, 1908, Columbia startled its competitors with the announcement that it was converting its entire catalog to double-sided pressings. Its hand forced, Victor followed suit on September 17, and Zonophone on September 24.34 Zonophone’s initial list consisted of 150 records, all coupled from previous single-sided releases and retailing for 65¢ each, just a nickel more than the single-sided Zonophones.

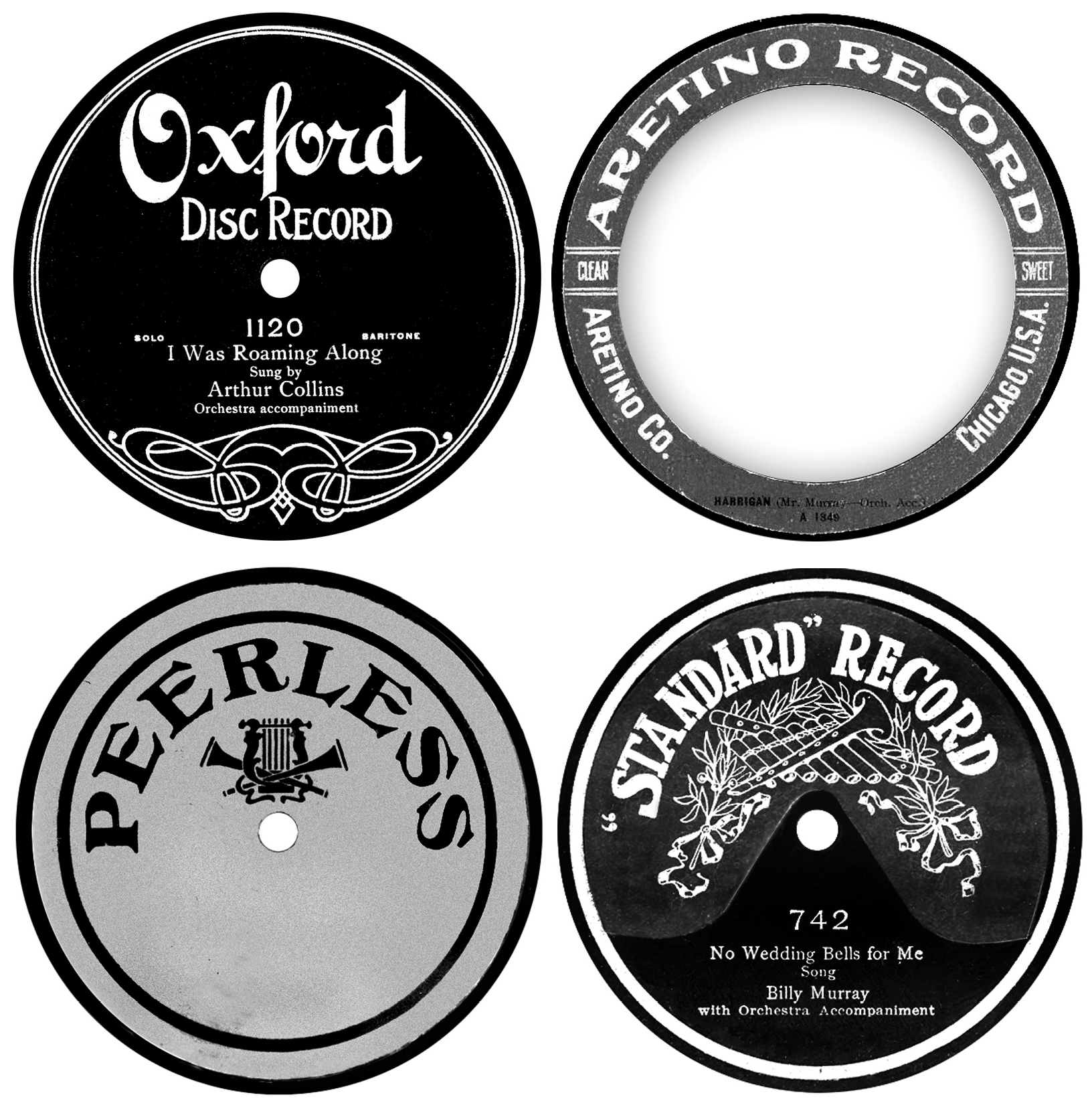

The announcement sparked a minor revolt among dealers, who complained that selling a second song for a nickel amounted to de facto price-cutting. The company offered an exchange plan that required dealers to purchase two new records in order to return one old one, to little avail. Once the offer expired on November 1, dealers were left with obsolete stock that was still subject to strict price controls. Universal cut the retail price of a single-sided ten-inch disc to 50¢ on October 1, then reluctantly agreed to allow dealers to sell the single-siders for 40¢ — not a great inducement for customers, when two songs could be had for 65¢ on a double-sided disc. The company’s mishandling of the situation caused some dealers to drop the line, and at least one lawsuit was filed. It is likely that the third-party paste-over labels from this period (like Peerless and “Standard” Record) were attempts by dealers to dispose of old single-sided inventory, rather thinly disguising the records so they could be sold below the list prices mandated by Universal.

Universal claimed that its first double-sided discs would ship “around October 1,” but newspaper advertisements suggest the records did not begin reaching dealers in any sizeable number until Thanksgiving week. Like Victor, Zonophone had been caught off-guard by Columbia’s announcement. It had already begun pressing its later-winter releases, in single-sided form, when the news broke. As a result, the final single-sided Zonophone discs were included in the first two double-sided lists, in December 1908 and January 1909. The first complete catalog of double-sided discs, “gotten up with velvet cover” and listing five-hundred records, went to press at the end of January and was released in March.35 The new double-sided discs were given a completely redesigned label, featuring the infant-and-phonograph trademark that Zonophone had been using in its advertising since 1907. Like its competitors, Zonophone at first filled its catalog by simply coupling its previous single-sided releases. Some artist credits were altered on the new couplings, most notably that of Hager’s Orchestra, for which the Zonophone Orchestra name was substituted.

Zonophone’s double-sided discs were hastily announced in September 1908, in response to Columbia’s surprise launch of the Double Disc. The original 1904 label design (left) was retired, and the double-sided discs were given a new label that incorporated the “On Speaking Terms” trademark.

At about the time it introduced double-sided pressings, Universal began to supply single-sided pressings from Zonophone masters to several retailers for sale under their own labels. The largest client by far was Sears, Roebuck & Company, which offered a large selection of Zonophone recordings under their popular, cut-rate Oxford label. Zonophone’s first Oxford series, which was made up of rather outdated material, bore the same catalog numbers as the corresponding Zonophone issues. A second series, produced after double-sided discs had been in production for some time, contained more timely material but took a strange approach to assigning catalog numbers. Oxford continued to use Zonophone’s catalog numbers, but since Oxford records were single-sided, Sears had to append the Zonophone side designations to distinguish between the identically numbered issues in its list. The last of Zonophone’s Oxford releases, listed in Sears’ Summer 1910 catalog, came from recordings that had been issued in March of that year.

Universal also briefly supplied the Aretino and Busy Bee labels, which were used in premium schemes in which a phonograph was given away, or sold very cheaply, when a specified number of records were purchased. The phonographs were modified to prevent the use of standard records — with a large rectangular turntable lug on the Busy Bee machine, and a three-inch spindle on the Aretino — which supposedly ensured a captive audience for the matching records. The artists were often anonymous on Oxford and the other client labels.

In the meantime, Columbia had continued to challenge Universal in the courts. In 1907 Columbia had obtained an injunction against the Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing Company, charging infringement of its Jones patent.36 However, Columbia then made the misstep of allowing Universal to violate that injunction, on the widely held supposition that Universal was owned and controlled by the Victor Talking Machine Company. Had that been the case, Universal might well have been covered under Victor’s and Columbia’s cross-licensing agreement of December 1903. Unfortunately for Universal, its status as a fully independent company was disclosed by Victor and Universal executives during the course of some unrelated litigation in Chicago. Armed with that evidence, Columbia reneged and applied to the U.S. Circuit Court, demanding that the 1907 injunction be enforced, that Universal Talking Machine be held in contempt, and that an accounting be made of all Zonophone records manufactured since the 1907 ruling. In denying Columbia’s motion on August 17, 1909, Judge Howe noted,

The only thing plain is that the Universal Co. was given some license to violate the terms of the injunction of 1907. Now, it is said, they are violating it too much. Parties who agree to a violation of an injunction cannot expect the summary and drastic remedy of contempt when they disagree about the extent of the permission.”37

Columbia persisted, however, setting off a succession of suits, counter-suits, and appeals. Facing continued litigation, Johnson finally decided to bring Zonophone under Victor’s control. In a telling sign, a Victor-style patent warning was added to the labels, conspicuously coiled around the outer edge. In January 1909, according to the memoirs of recording engineer Harry Sooy, it was decided that Zonophone’s recording activities would be moved to the Victor studios.38 No immediate action was taken, and Zonophone’s studio at 256 W. 23rd Street (New York) remained in operation for another year. Pressing, however, was taken over by the Victor plant at around that time.

The transition to full Victor control came in 1910. In January The Music Trade Review reported that the entire Zonophone operation was being moved from Newark to Philadelphia, just across the river from Victor’s Camden headquarters. The same report noted that Zonophone’s 23rd Street studio would be closed, and that its recording activities would be moved to Camden,39 more than a year after the initial decision to do so had been announced. Zonophone’s studio probably closed in February 1910, based on a report that there would be no May list of records due to the transition.

Zonophone’s June list contained a number of records pressed from Victor’s own “B-” series matrices, none of which were issued on the Victor label. There is nothing on the labels or in the wax (or in the surviving Victor files, for that matter) to indicate that Victor recordings were used, but test pressings tell the tale. Given the loss of Zonophone’s files, and lack of markings on the pressings, it is impossible to determine how many Victor “B-” masters found their way onto Zonophone discs during this transitional period, but approximately a half-dozen instances have been confirmed from test pressings so far.40

In the same month those records were released, Victor took over Zonophone’s recording operations and started a new “Z-” matrix series reserved especially for Zonophone. Fortunately, the 1910 ledger covering these matrices has survived (although the 1911–1912 ledgers have disappeared), and they provide some insight into Victor’s Zonophone output. The “Z-” masters were purely Victor products, recorded in the company’s Camden and New York studios using Victor engineers, conductors, and accompanying personnel. Many Zonophone employees were simply laid off, but Victor provided new jobs to several key personnel. Recording engineer Henry J. Hagen was assigned to Victor’s experimental laboratory at first, then was assigned the position of “traveling recorder” for the Export Department, the same job he had held before his promotion to Zonophone studio manager in 1906.41 Musical director Edward King was put in charge of the New York studio’s house orchestra and eventually became a Victor recording supervisor.42

The new arrangement put Victor in the awkward position of competing with itself rather than with an independent subsidiary. A comparison of the Victor and Zonophone popular catalogs of 1910–1912 shows many instances of performers and studio personnel duplicating their efforts, making recordings of identical selections for both labels at separate sessions, sometimes held months apart. As the Zonophone line became increasingly redundant, it appeared at times that Victor was doing its best to help it fail. Zonophone products had been widely advertised and creatively marketed under Universal’s control, but Victor did little to market or promote the records. By 1912 the ethnic and classical catalogs had been largely abandoned, and new popular-catalog releases had fallen to a monthly average of only fourteen records, ten less per month than in 1911.

The new arrangement also did nothing to stop Columbia’s quest for an injunction. Faced with falling sales, ongoing legal costs, and the prospect of an adverse ruling at Columbia’s hands, Universal’s owners finally capitulated. On May 27, 1912, the New York Times carried notices to stockholders of the Universal Talking Machine and Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing companies, advising that a meeting was to be held on June 17, 1912, “for the purpose of voting upon a proposition to dissolve said company forthwith.”43 The stockholders agreed to dissolve the company and liquidate its affairs.44

The dissolution was formally certified by the State of New York on June 20.45 Dealers and customers were notified of the action in a letter dispatched on June 28, which advised placing any final orders as quickly as possible. The letter also noted, “We will not issue any new records, the July list being the last.” But no new July list was forthcoming, and the June 1912 releases were Zonophone’s last. The Zonophone masters were ordered to be scrapped, the machines were remaindered, and American Zonophone was no more. The trade papers, which had once covered Zonophone’s activities so zealously, devoted a single paragraph to its passing.

Notes

1 “Talking Machine Agreement.” Music Trade Review (June 9, 1900), p. 24.

2 Bell, C.A., and S. Tainter. “Recording and Reproducing Speech and Other Sounds.” U.S. Patent #341,214 (filed June 27, 1885; issued May 4, 1886).

3 The Universal Talking Machine Company then became the sales arm of the Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing Company.

4 “Now After the Dealer.” Music Trade Review (January 3, 1903), pp. 39, 41.

6 “A Talking Machine Consolidation.” Music Trade Review (July 25, 1903), p. 24.

7 “Prescott Severs Connection.” Music Trade Review (August 8, 1903), p. 35.

8 “No Positive Statement — The Talking Machine Men Will Not Talk, But Something May Happen Very Soon.” Music Trade Review (August 23, 1903), p. 29.

9 “W. Barry Owen’s Moves.” Music Trade Review (August 8, 1903), p. 35.

10 “News from Germany’s Capitol.” Music Trade Review (February 13, 1904), p. 39.

11 Douglass, Leon F. Letter to the trade (October 7, 1903). Bryant archive, Mainspring Press.

12 Auburn, suddenly left with no record-pressing business, soon set up its own recording company in the guise of the International Record Company (Albany, New York), which produced Excelsior records and an extensive line of client labels until being shut down by for patent infringement in 1907.

13 “Zonophone Records. Some New Nine-Inch Creations Which Are Highly Spoken Of.” Music Trade Review (May 7, 1904), p. 45.

14 Untitled notice. Music Trade Review (June 18, 1904), p. 37.

15 New Style Zonophone with Tapering Tone Arm.” Music Trade Review (November 19, 1904), p. 111

16 Untitled notice. Music Trade Review (December 24, 1904), p. 44.

17 “Legal Notices.” New York Times (February 27, 1905), p. 9. National Gramophone was not formally dissolved until 1908, at which time their patents and “book containing formula for making original (master) Zonophone records” were offered at public auction (“Legal Sales,” New York Times, April 24, 1908, p. 13).

18 “New Zonophone Catalogue.” Talking Machine World (December 15, 1905), p. 38.

19 “Disc Record Prices Reduced.” Talking Machine World (December 15, 1905), p. 5. Premium schemes varied greatly, but many involved the customer earning a “free” or deeply discounted phonograph by purchasing a specified number of records.

20 “Universal Co.’s Fine Quarters.” Talking Machine World (January 15, 1907), p. 49.

21 “Orders Seven Full Carloads.” Talking Machine World (January 15, 1906), p. 25.

22 Untitled notice. Talking Machine World (April 15, 1906), p. 29.

23 Untitled notice. Music Trade Review (March 31, 1906), p. 46. Hager went on to serve as musical director for a succession of companies including Okeh, where he was responsible for the release of the first authentic blues records, by Mamie Smith, in 1920.

24 “B. G. Royal Now President of the Universal Talking Machine Mfg. Co.” Music Trade Review (November 24, 1906), p. 51.

25 “Henry J. Hagen Assumes Charge.: Music Trade Review (November 24, 1906), p. 49.

26 Untitled notice. Talking Machine World (November 15, 1906), p. 44.

27 “New Victor Records — November 1906” (monthly catalog supplement). Victor Talking Machine Co. (Camden, NJ).

28 Untitled notice. Talking Machine World (October 15, 1905), p. 13.

29 Untitled notice. Music Trade Review (December 17, 1904); clipping, n.p.

30 “Extra! Special! No. 2 Zonophone Records” (catalog supplement). Universal Talking Machine Co. (March 1908).

31 “Universal Co. Enterprise.” Talking Machine World (March 15, 1908), p. 63.

32 “J. D. Beekman Returns Ill.” Talking Machine World (April 15, 1908), p. 50.

33 “Universal Co. Activity.” Talking Machine World (May 15, 1908), p. 32.

34 “Double Zonophone Records.” Talking Machine World (October 15, 1908).

35 “Feinberg with Universal Co.” Talking Machine World (January 15, 1909), p. 59.

36 American Graphophone Co. v. Universal Talking Machine Manufacturing Co. 151 F. 595 (January 14, 1907).

37 “Jones Patent Again in Court.” Talking Machine World (September 15, 1909), p. 14.

38 Sooy, Harry O. “Memoir of My Career at Victor Talking Machine Company” (unpublished manuscript, Sarnoff Library, Princeton, NJ), p. 42.

39 “Universal Co. in Philadelphia.” Music Trade Review (January 22, 1910), p. 43.

40 The Victor ledgers state only that these recordings were “mastered,” without giving any indication they were assigned to Zonophone. The Zonophone ledgers were maintained separately from Victor’s, and those covering the transitional period are not known to have survived.

41 Sooy, op. cit., p. 44. Hagen died on September 29, 1912, soon after having returned from an extended recording expedition to South America.

42 King, who by most accounts was unpopular with co-workers and musicians alike, is remembered today primarily as the studio manager who ejected the now-legendary cornetist Bix Beiderbecke from his first Victor recording session, in 1924.

43 “Legal Notices.” New York Times (May 27, 1912), p. 15.

44 “To Dissolve Company.” Talking Machine World (July 15, 1912), p. 11.

45 “Dissolution Notices.” New York Times (June 25, 1912), p. 16.